The Hawker Nation: A Singaporean Food Odyssey

Leaving Bilbao, I stupidly lost my suitcase. I had to rush to security where they were already inspecting the 12 cans of anchovies from Getaria that I had in my luggage. They let me go with a jest, “Here’s the joker. We’ve solved the anchovy smuggler case.”

That left me feeling a bit paranoid. I landed in Singapore, and the first thing I heard at the airport was, “If you possess any kind of drugs, you will be executed.” For a second, I panicked. I was smuggling some vacuum packed Iberian ham for my friend Hannes, in addition to the anchovies. Would they execute me for that too? Southeast Asians love pork and anchovies. I briefly considered flushing it all down the plane’s toilets. The message was repeated several times, “If you have any kind of drugs, you will face the death penalty.” Well, nobody mentioned anything about introducing Iberian charcuterie or canned fish into the country.

The taxi taking me to the hotel gave me my first history lesson. “Singapore is a young country. During the 19th century, it was a British colony. That’s why we all speak English.”

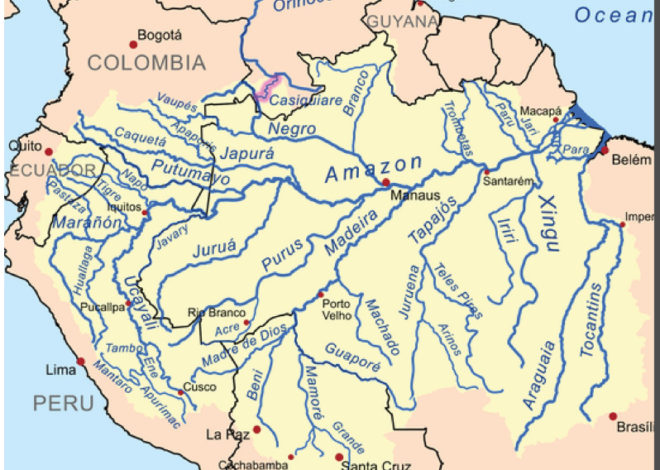

This strategically valuable colony drove transcontinental trade, attracting immigrants from all over Asia, mainly Chinese, Indians, Malays, and other groups. In 1965, Singapore gained independence from Malaysia, citing its multi-ethnicity as a reason to break away from a state that favored pure Malays. Singapore was expelled from Malaysia with the argument that it would not be able to survive on its own, which forms its foundational myth. So, we can say it’s a country built on its ethnic, religious, and cultural diversity, which, of course, is reflected in its cuisine.

I asked the taxi driver for recommendations on where to eat.

“Here in Singapore, you don’t need to go to restaurants; we have hawkers, it’s street food, cheaper and more diverse. Restaurants are for clueless tourists. The street food scene is of very high quality because no mediocre place survives. The competition swallows them.”

The word “hawker,” which I wasn’t familiar with, basically means a street food vendor, and it’s the predominant term here. A few years ago, to the amazement of some and the annoyance of others, the news went around the world that a street food stall in Singapore had received a Michelin star. By the time of my visit, they had lost it, but there are plenty of hawkers listed in the guide, and another one with a star has emerged.

Without a doubt, the Michelin Guide for Singapore is a good reference for finding great places to eat, but like any other guide, it’s tricky. The best thing is always to ask for recommendations through word of mouth.

After a couple of work meetings, I decided to check out a hawker court near the hotel. The variety was mind-boggling. There were 50 stalls offering Cantonese, Sichuan, Indian, pork offal, shark meatballs, Pakistani, vegetarian, drinks, Turkish, burger, dim sum, and countless other options.

I had arranged to meet up with an old friend, Hannes S., whom I had known since we were in primary school together, and who has spent a solid 10 years in Southeast Asia, 8 of them right here in Singapore.

“Here’s how it works,” Hannes explained. “They don’t give you napkins, so the first thing you do is buy them. They’re always sold at the drink stalls. You use the napkin packs to reserve your table. Just put your pack on the table and then go buy your food. No one’s going to take your spot. I even left my phone on the table while I went to order. People here don’t steal.”

Before coming here, I had gathered some recommendations for places to eat, or rather, I wanted to cross-reference the suggestions I had received earlier.

“Who gave you that crap? Those are all tourist traps. Don’t go to most of those places. You need to go where the taxi drivers eat. Street satays and beers on the street.”

Hannes revised my list as follows:

- Rice Chicken – Boiled chicken with greens and rice cooked in chicken broth.

- Bak Kuh Teh – Pork ribs boiled in a herbal “tea.”

- Chili Crab – I don’t know much about chili crab, but I can certify that the locals don’t go to Jumbo.

- Don’t forget Satay at Lau Pa Sat. Perfect after cocktails or to start a casual evening.

- C’est la Vie, just for the view, and Atlas has good Gins.

“Here, the market determines the distribution of stalls,” he said, “It’s like natural selection, that’s why they’re ethnically distributed fairly. If it were all Cantonese stalls, only the best would survive, and the others would be forced to close.”

My partner in this culinary adventure is Chef John Regefalk, conceived in Sweden, forged in Italy, and a traveler of over 50 countries, including the entire Southeast Asian region.

“You’ve been here before? When?” Hannes asked.

“More than 10 years ago,” he replied.

“Ah, my friend, this city has changed. It’s constantly evolving, especially in the last 10 years. Now, you can start a company in 20 minutes, and you can do it online,” Hannes told us. “I was with a startup in Malaysia first, but the conditions here are optimal. When I go to Germany, I feel like I have to downgrade my digital game. This country operates with the agility of a startup, in contrast to the dinosaur-like processes in Germany.”

In our first visit to a hawker court, we tried:

Abalone noodle soup: Noodles in a flavorful broth with unique-textured balls that look like human eyes, along with something resembling fish organs.

I asked John, “What’s this?”

“Don’t ask”

In our second stop, we had our first taste of shiny Cantonese-style glazed meats—ducks, pork bellies, and chickens hanging, glistening with a red sauce. It came with rice and wok-sautéed bok choy, topped with a sesame and peanut sauce. Delicious.

“Can’t we try rice chicken?” we asked Hannes.

“Rice chicken is usually for lunch, not dinner. Although nowadays, some touristy places offer it for dinner too.”

We did get to try Hainan-style rice chicken at a university canteen in Singapore Polytechnic. These canteens are like hawker centers themselves, reinforcing the idea that this foodservice format is part of the country’s food culture. Rice chicken is a Singaporean dish created by migrants from the Hainan province in southern China. Its beauty lies in its simplicity: boiled chicken that’s still juicy, and the cooking broth is used to make the rice. More sautéed leafy greens and the typical soy and spicy sauces to accompany it. Unpretentious and beautiful, it needs nothing more.

Hawker centers are a museum of creativity, multiculturalism, and culinary audacity. At our next stop, we encountered dishes like:

- Pork stomach soup

- Shark nuggets

- Oyster omelets

- Lamb marrow

- A billion varieties of soups

- Frog leg porridge

- Turtle soup

My mind wandered, imagining the origins of dishes like pork stomach soup, envisioning scenes of families designing business models around butchers’ leftovers, seeking to create a cuisine using less popular cuts, probably decades or centuries ago when hawkers literally roamed the streets with carts.

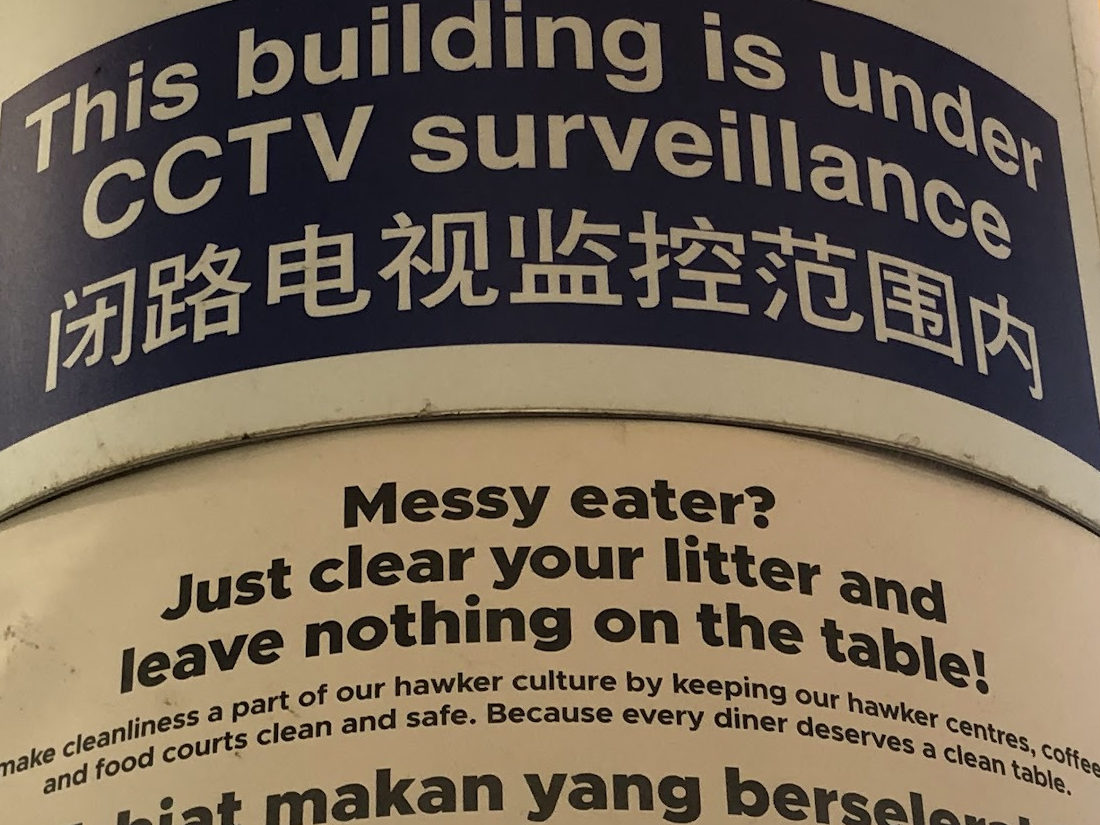

Hannes explained, “The letter grades displayed by each hawker indicate the level of hygiene and sanitation. You’ll see that almost all of them are A or B; nobody gets sick here; everything is super clean.”

Next night, we wanted to put the famous chili crab to the test. We went to a place called Holy Crab. I have to admit, at first, I had doubts about it because it was in a luxurious setting, mimicking the hawker center format but with small, stylish restaurants within the Kempinski Hotel. However, once we saw the menu, we realized it was a well-thought-out establishment. The restaurant offers five specialty crab dishes: Otak-inspired curry, salted egg yolk, thick Vermicelli, green curry, and black pepper versions. Their menu features various crab dishes, including unconventional ones like the Green Mumba, which uses green chilies instead of red in chili crab. Chef Elton Seah and Magic Faerie Joy lead the team at Holy Crab, focusing on delivering a gastronomic feast to diners. The crabs were massive.

I asked John, “What’s the kitchen like here? Can you imagine these fridges with hundreds of crabs like this?”

“Maybe they have them in a giant fish tank.”

For starters, we enjoyed some delectable bok choi sautéed until it had a slight char in a wok with a savory sauce made from chicken, pork, or both. Alongside it, we relished a plate of nasi goreng with shrimp and crab and a noodle tortilla.. They brought us bibs, gloves, clippers, and nutcrackers, all the gear you’d find in an operating room or in the hands of a serial crustacean disassembler. The process involved cracking, digging, and extracting the delicious and delicate goodness. It reminded me of my apprentice years when I extracted meat from thousands of lobsters. The baos they brought us to dip in the sauce were fried. We ordered both the classic and the green curry versions.

John said, “Mmm, this has the guanciale they put in everything here. The best seasoning; these Asians really know their stuff.”

Indeed, tofu has been a staple in Asia for ages, and using pork to enhance their sauces and stews is a common practice in their culinary culture, even in tofu dishes. The real star was the green curry sauce, the chef’s specialty, incredibly aromatic, almost like a puzzle to identify the various scents. It was a dark green that might scare European chefs, packed with aromas of lime leaf, kaffir lime, root spices like galangal and ginger, a good amount of spiciness, and a diverse forest of perfumes and scents to get lost in.

John mentioned, “Mmm…It has a hint of rose aroma.”

On the next day, I ventured out on my own to check off a couple more items from my bucket list: Michelin-starred pork noodles for 8 euros and herbal tea-infused ribs. Wise decisions, I must say. I started with Hill Street Tai Hwa Pork Noodle, the first family behind the Singaporean-invented dish, which gained worldwide fame as one of the first street food hawkers to receive a Michelin star. The Michelin panel included culinary icons like Anthony Bourdain, William Wongso, and Claus Meyer.

There was a small queue, and I ordered some crispy fish dorsal fin crackers—super crunchy. I also got a seaweed soup and the iconic pork noodle. The noodles were flat, like tagliatelle, but clearly made with alkaline salt, giving them their distinctive yellow color and, more importantly, a delightful elasticity. An elderly gentleman served the soups with little condiment bowls, wearing a smile that showed he truly enjoyed his work. The soup once again showcased the culinary boldness of utilizing every part of an animal, in this case, the pig.

I dived into the soup with my chopsticks discovering pork in all its forms; minced meat, thinly sliced pieces, succulent meatballs, delicate steamed dumplings, and flavorful liver—all an exquisite delight dressed in ancient, secretive sauces with a kick of Zhenjiang vinegar. And I savored every bite while seated at a simple plastic table, surrounded by local workers. I also ordered a seaweed soup, which felt like strands of nori covered in a rich broth.

Next, I went to Mr. Ng Siak Hai’s place, also known as Ng Ah Sio, who began working at his father’s Bak Kut Teh stall. It was located at the foot of Government Hill, which is present-day Clarke Quay along River Valley. The stall became popular and was known as “Foot of Government Hill Bak Kut Teh.” In 2006 it made headlines when it refused entry to the then Hong Kong Chief Executive Donald Tsang after closing hours.

Bak Kut Teh basically consists of ribs cooked until ultra tender and then served with an extremely aromatic broth. The name translates to “pork bone tea.” It’s known for its high-quality pepper aroma and hints of background chinese medicinal herbs. Like any recipe of this kind, each family has its variation. In this place, they take a minimalist approach, using only ribs and a clove of garlic in the broth. Delicious. The place is like a tea house, with an extensive tea menu, where the staff roams around with a teapot filled with broth to refill empty bowls.

From there, I met up with John at another market. Until then, we hadn’t tried any Indian dishes. The taxi driver had recommended ordering some stewed lamb bones. They brought us a red stew—excessively red, as if the cook had spilled the entire bottle of food coloring into it.

But no, that’s just how it is. Other places served it the same way. The stew was tasty. Suddenly, the gentleman serving us brought some straws and left them on the table. We were a bit puzzled. On the table next to us, a lady seemed entertained watching us and said, “It’s for sucking the marrow from the bone.” It was like the carnivorous equivalent of bubble tea. I still can’t understand why this hasn’t become a worldwide trend.

That night, we wrapped things up at the Satay Street in Lau Pa Sat. Once again, Hannes showcased his local expertise, teaching us how to order and correct the vendors when they didn’t get things right. This was one of the most beautiful hawker courts.

Hannes mentioned, “This place lost some authenticity after COVID, like many parts of the world. The pandemic hit vulnerable establishments like a hurricane. Nonetheless, there have been investors who are committed to preserving traditional places by sponsoring the families who run them to keep their successful secret recipes.”

Outside the market, there was a row of 500-meter-long grills, each specializing in satays, and about a thousand people sitting and eating. Satays are skewers of grilled meat or chicken. More recently, they added squid and prawns to the menu, but that’s not the most common choice. They come with essential condiment sauces and little bags of cooked rice that look like rice tamales, cut into cubes. The prawn satays were nothing out of the ordinary, and the squid ones were marinated with a super spicy paste. However, oh mama, the chicken and lamb satays were the real deal. Slightly spiced, with the ubiquitous sauce varieties.

We did our best, but we couldn’t try everything in this vibrant street food ecosystem in the city-state of Singapore, the hawker nation. Bit by bit, as you visit a country like this, your mental library of flavors and culinary concepts becomes a hill, just as the Malay proverb suggests.