Kuala Lumpur Blues

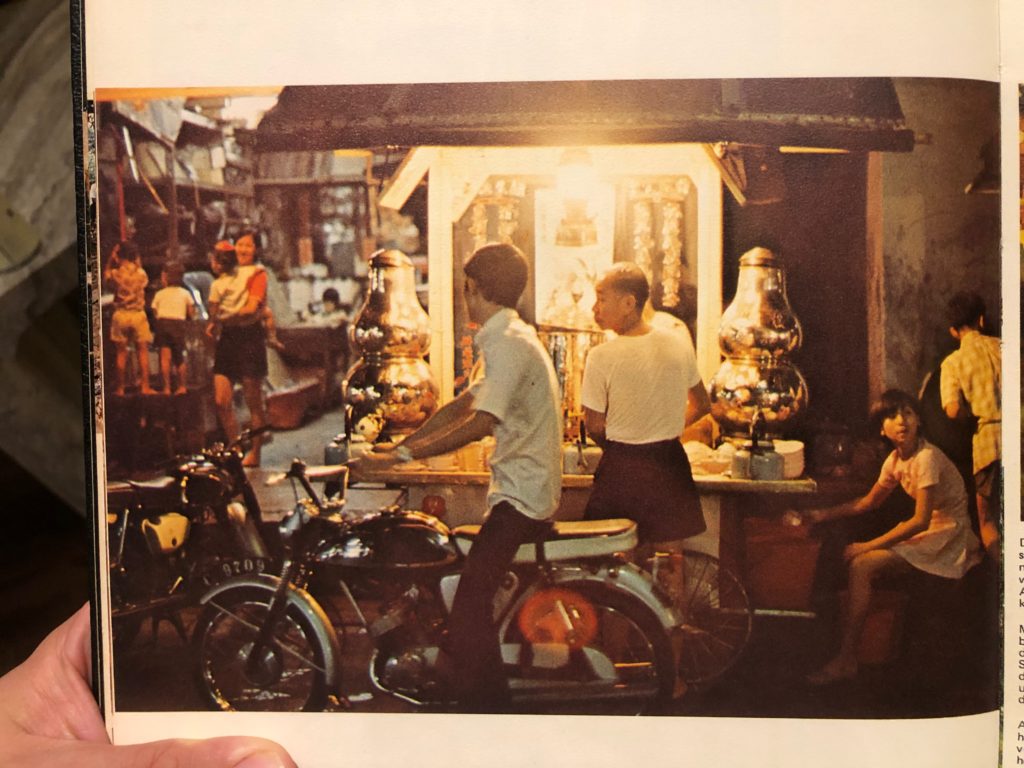

I land in Kuala Lumpur, and man, it’s a wild switch from Singapore. I take a cab from the airport and head downtown, cruising through these lush green expanses dotted with banana trees. There’s something about KL that takes me back to my roots in Caracas.

Malaysia and Singapore split paths in 1965. While Singapore sprinted towards modern industrialization with sweeping reforms, Malaysia kept grappling with internal political strife, the hangover of decolonization, and, clearly, some pretty corrupt leadership that’s left it with some socioeconomic shortcomings.

Bikes buzzing by, crafty monkeys thieving at Hindu temples, houses crumbling down. I stay in a hotel near Chinatown, and the street scene’s got it all: homeless people, buildings getting choked out by vines, a real vibe of grime and decay. Then it hits me like a ton of bricks, something I’d forgotten with all the work meetings cluttering my head. I felt like the world’s biggest idiot. So I text John who was still in Singapore.

“Man, I can’t believe I forgot. An old friend of mine, haven’t seen him in years, lives in Singapore now, and he’s made quite the name for himself as a chef, Ivan Brehm.”

“Oh? You’re friends with Ivan? He’ll be a host at the event tomorrow.”

What are the odds? John’s got a talk at Kita, this food event I’ll explain on later. I didn’t spend a second informing myself about the event I was attending. Ivan and I, we did time together in Mugaritz back in 2006. By the time Ivan joined the team, I was the oldest stagiaire, and it didn’t take long to see he was way more advanced then I was, culinarily. He had already worked at Thomas Keller’s Per Se in Manhattan.

My year at Mugaritz was like a strong line up of chefs who would become superstars on their own: Dann Hunter, Lucca Fantin, Alejandro Cancino, Paco Morales, Ollie Dabbous, Kamilla Seidler, Stefano Baiocco, Shinichi Sato, just to name a few. Ivan also belongs to that list. But the memories that stick aren’t about what we whipped up in the kitchen. It was the hangs at the apprentice house.

Photo: Shinichi Sato Frying chicken at the apprentice house in 2005.

They were really about the good times at home, going out to drink, bursting with laughter, talking about signature dishes, and looking at pictures of dishes from chefs we admired on a laptop.

I remember asking him about things about Per Se.

“So there was this time,” Ivan said, “I was wearing my apron backwards, with the ‘Special’ tag sticking out, right? And Thomas Keller walks by in the kitchen and goes, ‘What’s up with the apron? What’s that? Special?’ And then the head chef comes over and is like, ‘Yeah, chef, it’s because Ivan is very ‘special,” you know? He said it like my parents were paying for me to be there, right in front of fucking Thomas Keller.”

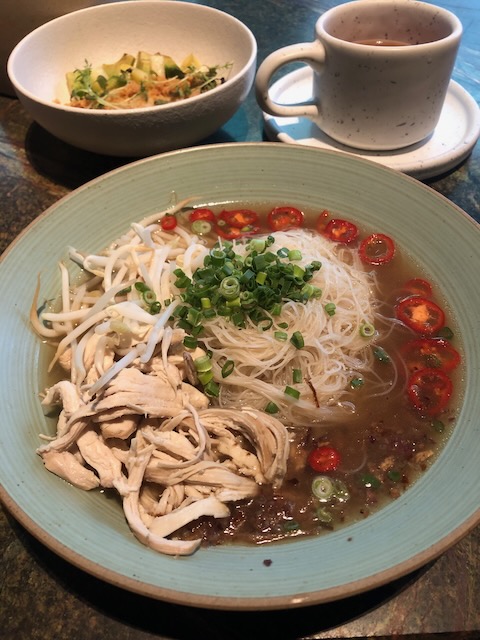

After John arrived from Singapore, we planned to meet for breakfast, but true to Swedish form, he was up two hours earlier than me, preparing his talk. So, I was going solo for breakfast.

Breakfast like a local. I ordered a Soto Ayam which is a chicken noodle soup with chilies. And then, boom, there’s Ivan, staying at the same hotel. I stared to make sure it was him. Would he remember me now that he’s famous?

“Oh my God, Erich! How’s it going? Give me a hug.”

It was a warm moment. We only chatted briefly—he was with a crowd—but we set up lunch for the next day.

“You’re looking good, man. Haven’t changed a bit, recognized you right away. Sure, let’s do lunch tomorrow, I know a couple of good spots.”

Since he was one of the moderators of the event, he was surrounded by various speakers and organizers. I joined them, talking about my recent culinary explorations in Singapore and my total newbie status with Malaysian food culture. That was about to change.

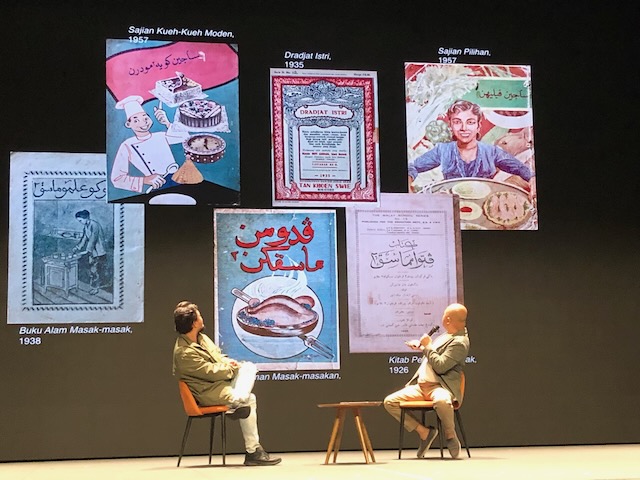

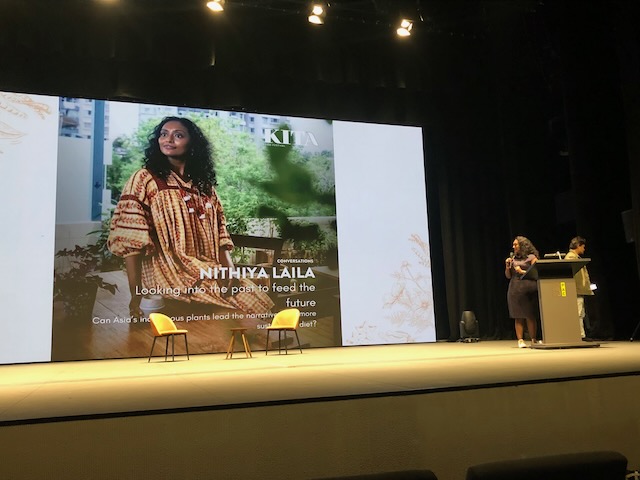

The event was set in a theater. Leisa Tyler, one of the ladies I’d had breakfast with was introducing speakers, and a guy in a military jacket and messy clothes, along with Ivan, were hosting. The lineup was killer. Local renowned chefs such as Darren Chin, Jennifer Kuah, and Raymond Tham discussed the culinary scene in KL. There were also, from anthropologists and sustainability techies to avant garde chefs like Chele Gonzalez and TV celebrity chefs like Diana Chan.

Most speakers were dishing on Malaysian food culture and its tight ties to Singapore because of their shared history. There were dissertations over who makes the best satay or chicken rice. Local presenters shared their first fiery encounters with spice or Indian and Chinese food, which, like in Singapore, also weaves into the local fabric.

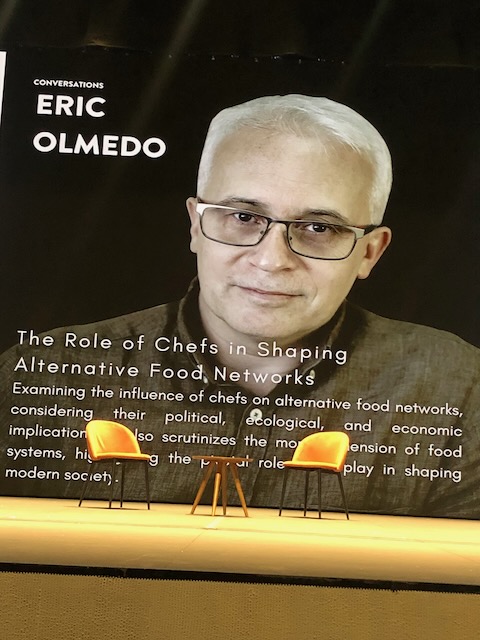

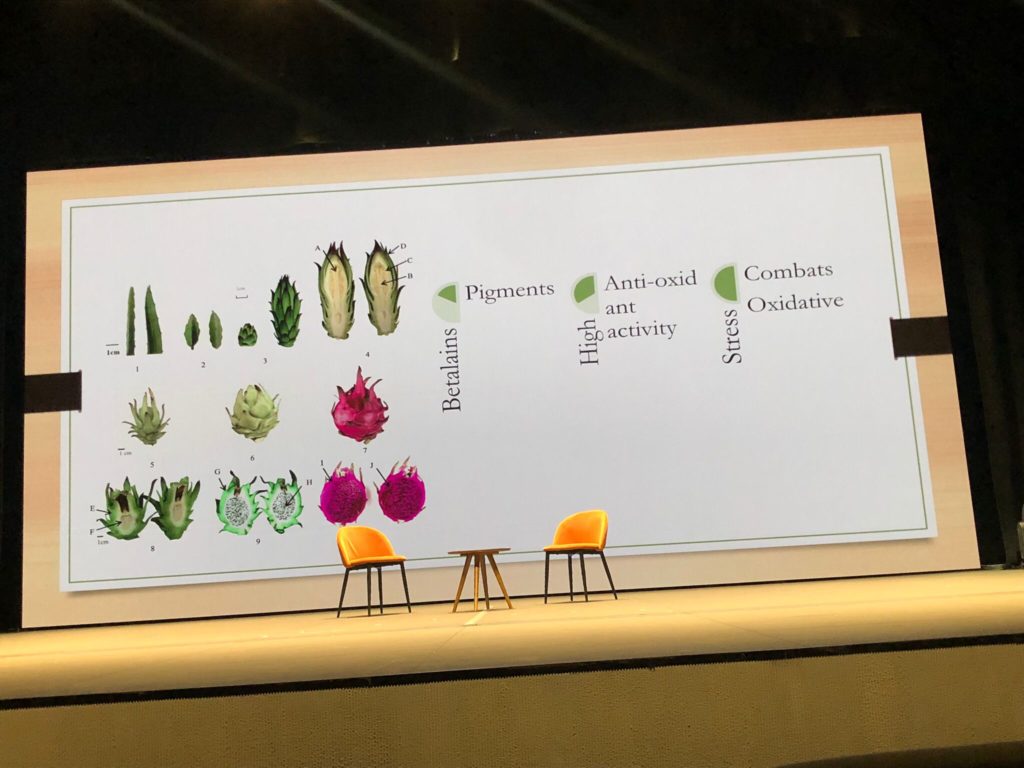

But the talk that got me was by an anthropologist, Eric Olmedo. He spoke about the social change that chefs can ignite. Vietnam had been growing dragon fruit massively for China, but when China suddenly switched suppliers, it left Vietnam in the void, especially hitting the Tay ethnic minority farmers hard. Olmedo’s work with these farmers and chefs to create new supply chains and new culinary applications for these products was truly inspiring. They started using the sprouts of the flower somewhat like a soft artichoke or a bamboo shoot. They managed to make dragon fruit sprouts a new trend in restaurants across Ho Chi Minh City, rebalancing the supply. An example of how these collaborations really can drive change.

The next day I cleared my schedule to meet with Ivan.

“I’m off for lunch, mate.” I tell him.

“Bubba, I think I need to rest. Not feeling super good,” he replies.

“Alright, but let me know if you’re up for tea, or soup in your room, or whatever. I just want to hang out and chat,” I say.

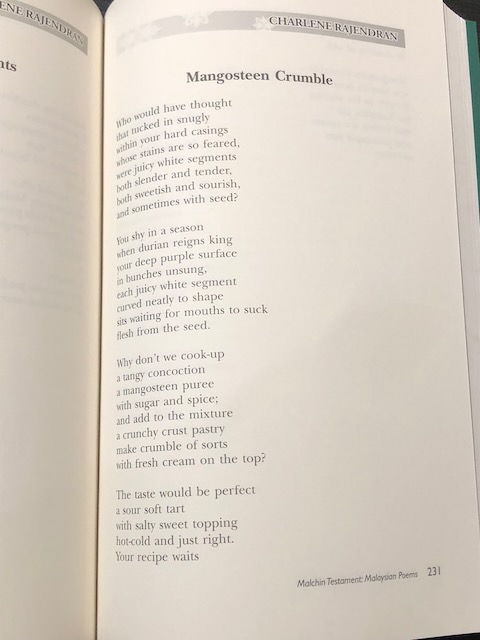

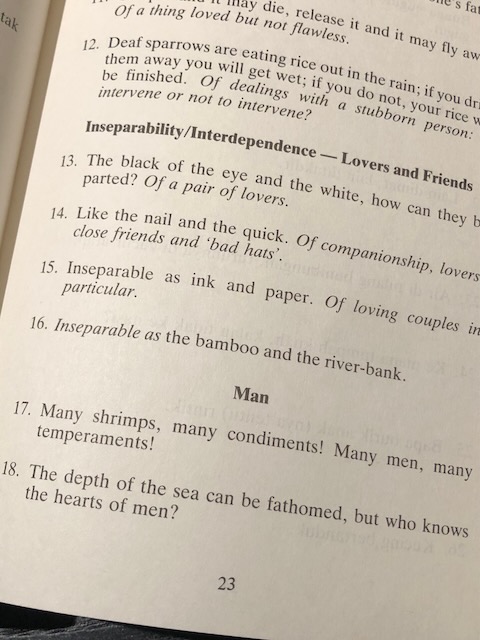

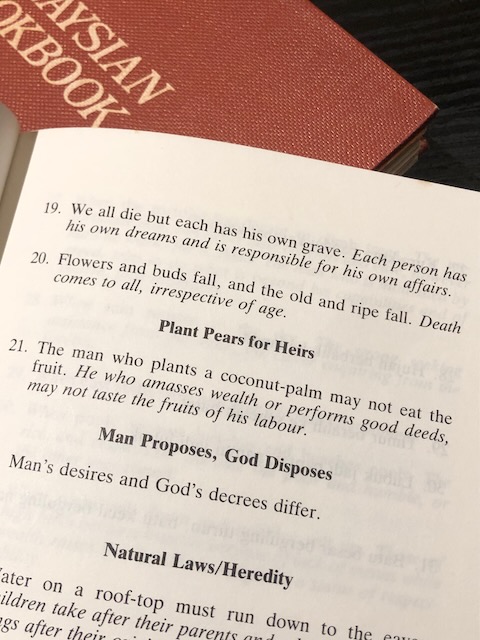

I spent my time in the hotel library working and, at times, randomly thumbing through books on cooking, poetry, and Malay proverbs. A few hours later, Ivan texts me.

“Hey Bubba, heading to Darren’s restaurant to grab some stuff then back to the hotel for a final walk around the neighborhood. Want me to buzz you when I’m back?”

“No way, man. I’m coming with you,” I reply.

“Okay. I’m booking a cab now. See you in the lobby.”

Darren, the guy in the military jacket and unkempt attire, one of the event’s organizers, had been kind enough to help me get a cab the day before. He’d mentioned owning a restaurant, but that was news to me. When I reached the lobby, Ivan said, “Hang on a sec, please,” and darted off, phone to ear, “Yes, spread those cherries out on a tray and hit them with vinegar in…”

Chef’s life.

Ivan Brehm is a character, hard to describe. He’s like a Brazilian, German, Gandhian poet, an anthropologist, a soul of kindness, sometimes a clown, yet he exudes calm and positive vibes. He’s just an outstanding human being who happens to be a chef.

Once he finished his call, I talk to him in the cab.

“Dude, how’ve you been? Tell me about your work at Nouri. What’s your cuisine? I’ve seen you’ve become quite the sensation in Asia but honestly, I don’t know much.”

“I’ve been delving into food connections. You see, Singapore has acted as a node for many cultures, and we aim to reflect that on the plate. That is, our creative process starts with some anthropological reference, actually our researchers are usually anthropologists, we take care of the culinary aspect ourselves.” Ivan explains.

“That sounds incredible. Do you share these insights with your guests?” I asked.

“You know what? At first, we did, but it didn’t go down well. Diners don’t want to be lectured during their meal. Partly because they don’t want to be disturbed, partly because they don’t want to feel ignorant. So, we stopped. But in the end, that’s not even the point of our cooking. It’s not necessary to add a narrative layer; if we complete our search process correctly, the dish becomes self-explanatory and tells a universal truth,” Ivan said.

“Wow. I get exactly what you mean,” I said.

“That puts you among the few who do. It’s super tricky to explain these things,” Ivan remarked.

“Do you have an example of that?” I asked.

“Look, I can make a potato salad, right? I cook my potatoes properly, add the right amount of salt, acidity, fat, etc., and that itself works, it’s a dish. But the moment I add an aromatic, say, a spice endemic to a neighboring island with a scent that takes you out of your comfort zone, we’ve added a completely different and memorable layer. We recently made a dish that a Filipino couple tried. The man said, deeply moved, it reminded him of his grandmother,” he told me.

“That’s the highest praise any cook can receive,” I said.

“Sure, but none of us involved are Filipino, and there was no tradition there in our research, in our process, but somehow it led us to a common discovery with that mans grandmother,” he said.

“Hold on, give me a minute,” he took his phone and started talking. “No, that’s not the right supplier, call this one, I’ll pass you the number…”

Ivan was constantly running his restaurant remotely.

“Man,” I said, later “it feels like, just now, we’re only now truly stepping into a post-COVID new normal.”

“Well, if you can call this a normal, with all the powers that be stirring up wars, inflation, pollution, and crap. We all just want to live in peace, raise a family, and be happy, and these bastards won’t let us,” he says.

We head up to an office block, aiming for the back door where suppliers come and go, dodging boxes and the kind of random stuff you’d find in the storeroom of an unglamorous market.

“I’ll grab what I need from the restaurant and then we go get lunch,” Ivan tells me, but the back door’s a no-go, so we circle around to the front and entered through the lobby, which, in contrast, was the picture of pristine offices. We took an elevator up to the 48th floor, and the doors open to a floor leading mind-bending high-end restaurant. Chefs, about 10 of them, working like clockwork.

Ivan waltzes in, home turf style, walks into into who probably is the head chef. A brotherly hug, a pretend nipple twist, and the jokes are flying. Laughter erupts. The welcome’s warm. Clearly, he has cooked with this crew before.

“Meet my mate Erich,” he introduces me. “Gonna show him the kitchen.”

The place is vast. A super-kitchen with stations galore, a grill space, an extra production kitchen. He fist bumps various chefs, giving me the rundown.

“This guy’s a beast in the kitchen, watch him go.Hey, how’s it going? Meet Erich, he’s visiting for a few days.” Then to me, “Hey, you want to book a table?”

“Sure, we fly out tomorrow but can come by for lunch.”

“They only open for dinner.”

“Well, why not? Could be our last supper in Asia.”

Next, Ivan takes me to a small test kitchen beside the main service area, where the restaurant manager’s on a laptop amid advanced lab gear and ceramic fermentation jars.

“Can we book him in for tomorrow? They fly out at midnight? Okay, great. Can I show Erich the dining room?”

He leads me to the dining area, an exquisitely designed space with massive windows framing the Petronas Towers and the city spread out below. A beautiful dinning room with robust wood counters and badass works of art that resemble cave paintings, the vibe is dialed into the details, tactile heft of local wood and curated chaos of Malaysian motifs.

“Stunning, right? Beautiful spot. And you know what’s the best? Darren’s running it and he’s not a fucking idiot. Do you know how rare that is? To find a place like this not headed by a jerk?

Turns out, Darren Teoh, the event’s host from yesterday, the guy in a military jacket and messy clothes who I pegged as a somewhat shy food journalist oozing humility, is actually the brains behind what some call Southeast Asia’s Noma, Dewakan. He’s also the co-founder of the event, Kita Food Festival. I walked out of there, mind blown, thrilled for tomorrow’s dinner.

We went to Chinatown, for my last meal with Ivan.

“I’m gonna order a bit of everything. The food’s good here. They’ve got these spinach, egg and tofu grilled dumplings, handmade Chinese noodle soup, spicy eggplant—nobody does eggplant like the Chinese. There’s this killer duck soup too, and we gotta get the rice and the cucumber salad with beef that comes with a broth. What do you want to drink?”

We grabbed canned oolong. The feast arrives, and the rice is like what they call “arroz tres delicias” in Spain.

“Damn, this rice tastes way better than any I’ve had before,” I tell him.

“It’s the MSG, buddy,” he says, giving a nod to my pal Phil… ‘the good stuff’.

“Hold on a sec, sorry,” he says, grabbing his phone. “Yes. Send it to the restaurant on Tuesday, same batch as last time. Excellent.”

He hangs up and tells me, “Caviar. I’m getting caviar for the restaurant.”

“There’s good caviar in Asia?” I ask. “I’ve been told that Noma used Mongolian caviar for their pop-up in Mexico.”

“The best caviar in the world right now is Chinese. And yeah, there are different producers across the region.”

Then we reminisce over old tales.

“Remember that chef who was a mess?” I asked him,

“Yet, I must say, there was a kind part in him,” he says “and a phrase I’ll never forget: when someone started to work sloppily, he’d approach and say, ‘Please, with poetry.’ That phrase has stayed with me over the years. ‘con poesía‘” he repeated in spanish.

“Those were good times, I have such great memories,” I told him. “Passing through Mugaritz is a transformative experience.”

He agreed, “Yes, I don’t know anyone who’s come through there without it changing them in some way.”

“Who else?” he said “Ollie Dabbous, was the best staigiaire in the kitchen. We all wanted to be like him. Remember when we hopped into a shopping cart and he pushed us with his car? I don’t know what we were thinking; that shit is incredibly dangerous.”

I left Ivan in the hotel lobby, on the phone with his restaurant team, as we said our goodbyes. I hope it won’t be 20 years before we see each other again.

Finally, next evening, the big night at Dewakan. We arrived at the restaurant with our luggage; we would head straight to the airport afterward.

To be continued…