Vietnamese Flavors from Berlin to Paris

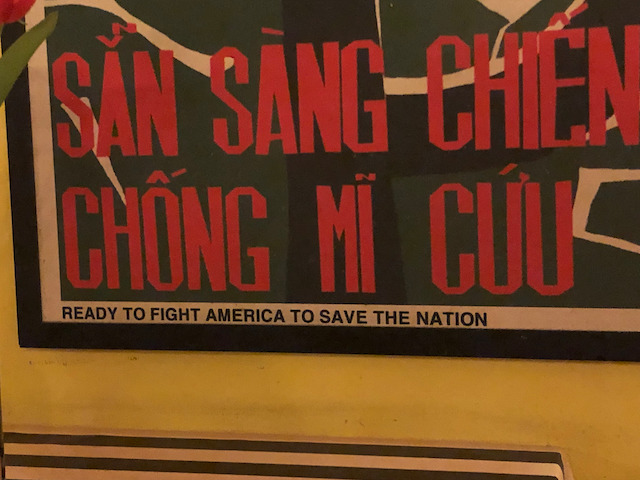

I’ve never been to Vietnam, and I don’t know any famous Vietnamese chefs, except for Nguyen Thi Thanh, the lunch lady. In Venezuela, I grew up around Chinese and Japanese people to some extent, but I don’t recall connecting with people or restaurants from other Asian countries in the ’90s and early 2000s. My only reference to Vietnam was through violent pop culture: The burning monk on the cover of Rage Against the Machine, movies like Platoon, Apocalypse Now, and Full Metal Jacket. I don’t remember ever encountering Vietnamese people in my life or having Vietnamese food until I arrived in Berlin.

My first interaction with the Vietnamese community was through a common ingredient: banana leaves. Banana leaves are an essential component of the Venezuelan Christmas dish called “hallaca,” which is a tamale wrapped in these leaves with a filling enriched with raisins and pickles. I remember packaging and sending banana leaves by mail to friends’ mothers all over Europe. During a brief period, I worked on a Venezuelan restaurant project where we made hallacas. It was there that I discovered the “Great Asian Market of Berlin in Marzahn,” which, to my surprise, was predominantly Vietnamese. The major Asian distributors, Vin Loih and Dong Xuan, are also Vietnamese.

As it turns out, due to bilateral agreements between Vietnam and East Germany, a bridge was established that led to a significant influx of refugees during the Vietnam War. These refugees played a role in popularizing their food culture worldwide. A second wave of immigrants arrived in the ’80s under the “guest worker” agreements, again within the framework of collaboration between nations in the Soviet bloc.

One day, I stumbled upon a street festival with entire Vietnamese neighborhoods closed off. It didn’t take long for Vietnamese cuisine to become one of my favorites whenever it was available. My ideal Vietnamese menu would start with:

Gỏi cuốn, also known as summer rolls: It pisses me off me when a menu says “Vietnamese rolls,” and you get fried rolls. For me, the Vietnamese rolls are the summer rolls. It’s simply brilliant to turn a salad of rice vermicelli with pork, chicken, shrimp, mint, and basil into finger food wrapped in rice paper. They are sometimes served with peanut sauce, but I prefer them with nuoc cham, a tangy sauce made with chili, lime and fish sauce.

To me, Vietnamese cuisine is all about greens and whites: a vibrant tapestry of freshness, rice in the shape of sticky surfaces, the gentle embrace of mint, basil and cilantro, some chili, lime and boiled meats and seafood.

And don’t forget the salty limeade (Nước Chanh Muối). Pure freshness, vibrant flavors, bursts of acidity. The best one I tried was at Mrs. Pho in Singapore, along with a green mango salad dressed with fish sauce and enriched with bits of cooked pork.

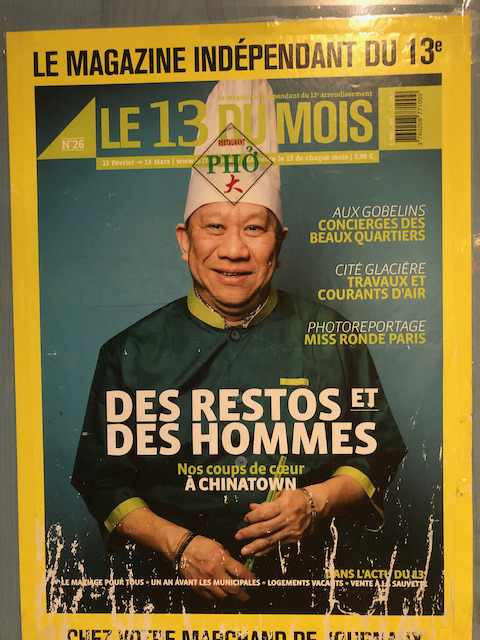

In Paris, I had Ba’nh cuo’n for the first time at a restaurant called Pho Tai, which I was told is often frequented by Alain Passard. It’s a giant pancake made from fermented rice batter filled with a pork pâté and mushrooms. I wonder if that is also a French influence, similar to the baguette in banh mi, or the fact that Vietnam has a strong coffee tradition.

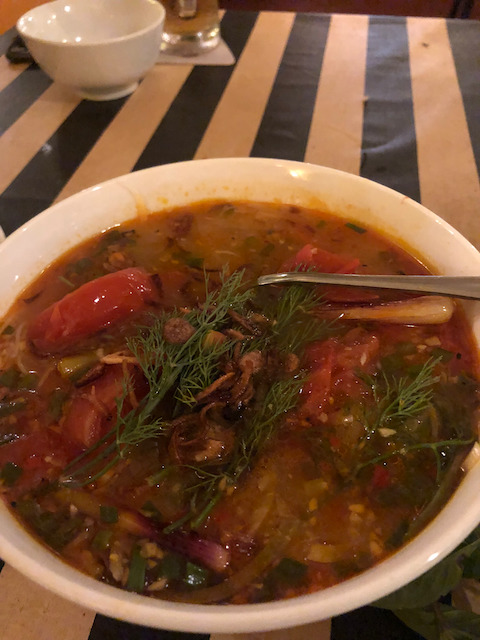

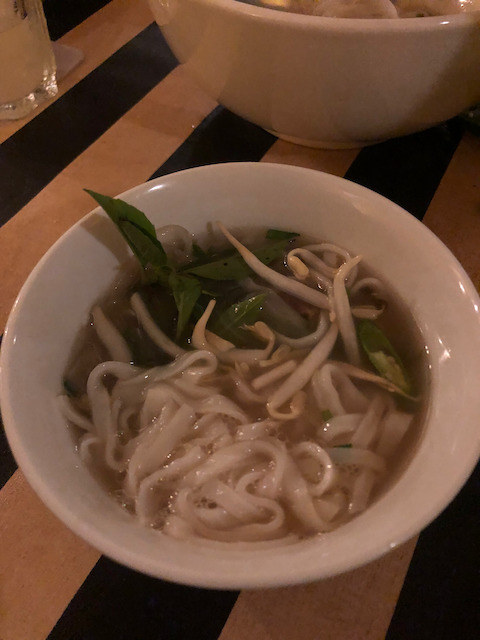

Then there’s the queen of rice noodle soups, Pho, created in the city of Nam Định in northern Vietnam.

Phở’s origin story has a bit of French and Chinese flavor. Around the early 1900s the French in Vietnam created a demand for beef that led Chinese workers to start cooking up a dish similar to phở, called ngưu nhục phấn. Street vendors would carry their gear on shoulder poles, one cabinet held a big pot bubbling away on a wood fire, while the other was full of noodles, vegetables, spices, and everything needed to pull off a bowl of phở. In the 50s when Vietnam got split in two, over a million people fled from North to South Vietnam, popularizing the soup also in the south. In the 1970s, as Vietnam’s refugees scattered worldwide, so did the love for Pho.

The secret lies in the base broth, typically made with beef bones, oxtails, flank steak, charred onion, charred ginger, and a blend of cloves, star anise, coriander seed, fennel seeds, cinnamon and black cardamom, which subtly emerge among the meaty flavors. All of this is topped with a generous handful of fresh herbs, a tangy kick from lime juice, and thin slices of meat that cook in the same broth, like shabu shabu. The best one I ever had was at Sao Nam in Kuala Lumpur.

From the streets of Berlin to the vibrant kitchens of Paris and Kuala Lumpur, each dish I’ve savored tells a story of tradition, migration, and cultural cross pollination. The epic tale of Vietnamese cuisine shows us that gastronomy isn’t just a source of identity and pride, but also an exportable treasure, revealing the most affectionate and honest face of a culture.