The Mystery of Gong Fu Tea

My first time in Asia, and I found myself entering a traditional Chinese tea house, “The Chapter” in Singapore. The place felt like it came straight out of a Chinese fairy tale.

Stairs led to a corridor with private chambers, each with individual tables for savoring fermented leaf broths and, why not, a bit of gossip. The tea master, known as “cha shi,” approached us in a traditional Taoist attire, handing us an extensive tea and yumcha menu.

Clueless, we let him guide us, “Do you prefer something fruity, herbal, earthy, or sweet?” We chose an earthy oolong, and he gracefully withdrew. Traditional Chinese calligraphy adorned the walls, alongside a photo of Queen Elizabeth II sipping tea at the venue in the ’80s.

Upon his return, the tea master presented our first set of instructions. First, the water temperature. He poured cold water into a large Chinese iron jar with choreographic flair until the digital thermometer reached the right temperature.

Then, he poured the hot water into an infusion jar, setting a timer for 3 minutes before transferring it to another jar for serving. We had two tiny cups, even smaller than shot glasses. The first resembled a tube, and the master instructed, “This is just for smelling.”

We brought it to our noses and inhaled the aroma. Then, we poured the tea into the second cup, shaped like a miniature bowl. “This is for drinking,” he instructed, demonstrating how to hold it. It reminded me of how Jackie Chan held his glass in ‘The Drunken Master.’

Ladies are allowed to lift their pinkies, but not gentlemen, he noted. With a sip, I lost my self in a well of aromas and wisdom. “Now, smell the tube again,” he instructed, and the fragrance had transformed. “That’s it. Repeat as many times as you like.” And so began my obsession with tea. Upon returning home, I discovered this tea-drinking art was known as Gong Fu Tea.

I got Chinese iron teapots, filters, and began using the cups I brought from Asia. If you’re a Westerner starting to explore tea, a great beginning is “The Book of Tea” by Kakuzo Okakura.

He, a Japanese man who studied arts, traveled to Europe and the United States in the late 1800s before returning to Japan, wrote the book to introduce Westerners to the secrets of tea appreciation. A recurring theme throughout the book is that the act of tea-drinking is an art. This phrase transports me to feudal Japan, with dirty streets, gambling dens, brothels, and katana-wielding warriors. In such a context, creating a ceremonial space to escape the noise and focus on an immersive sensory experience, crafted by masters who understand the parameters of brewing a great cup of tea without timers or thermometers, becomes an art form. For Okakura, the tea-master is an artist and philosopher, transcending the mere preparation of tea to embody art and aesthetics. It’s no coincidence that this book served as an entry point to Eastern philosophy for the German philosopher Martin Heidegger, whose philosophy was heavily influenced by Eastern thought.

Tea is essentially a leaf, first fermented to develop complex aromas and then dehydrated to preserve and transport it. Varieties like Earl Grey were discovered less than two centuries ago by a Scottish adventurer named Robert Bruce who noticed tea-like plants growing wild near Rangpur in 1823 during a trading mission. I think there’s still great potential for developing new teas from uncommon plants, as noted by gastro botanist Blanca del Noval. “We’ve experimented with apple and cherry leaves, applying tea fermentation techniques, and achieved great results.”

Here are some common misconceptions, from which I’ve had to liberate myself as well. If you brew your tea with boiling water, steep it for longer than necessary (usually not more than three minutes), or add sugar to your tea, I regret to inform you that you know nothing about tea appreciation. Sorry.

Tea it’s all about subtlety, not overpowering the water with aroma, giving it just the right infusion at the correct temperature to appreciate the depth of flavors produced by the fermented leaf. Adding sugar to tea is like trying to fix a ruined thing, balancing overly steeped bitterness, just like honey or lemon.

Regarding this matter, Elena Romeo, the world’s first doctor in gastronomic sciences, published a paper on how the combination of tea and cookie aromas affects our liking and perception of sweetness. The study, concluded that when the aromas blend well, we tend to like the combination more and perceive the cookies as sweeter, even if they don’t contain more sugar. What it means is not only that it is not necessary to add sugar to tea, but also that the right unsweetened tea can enhance the perceived sweetness of cookies.

Half the world calls it “tea,” while the other half says “cha.” This discrepancy arises from linguistic variations. In Min Nan Chinese, the word for tea is pronounced as something resembling ‘tê,’ which spread through maritime trade routes to become ‘tea’ in English, ‘thé’ in French, ‘tee’ in German, and ‘thee’ in Dutch. In Mandarin Chinese, the word for tea is pronounced as ‘chá,’ which spread overland via the Silk Road, influencing Central Asian, Eastern European, Persian, and Arab languages with words like ‘chai,’ ‘çay,’ and ‘shai.’

So, why say “chai tea,” which is as absurd as saying “queso cheese”?

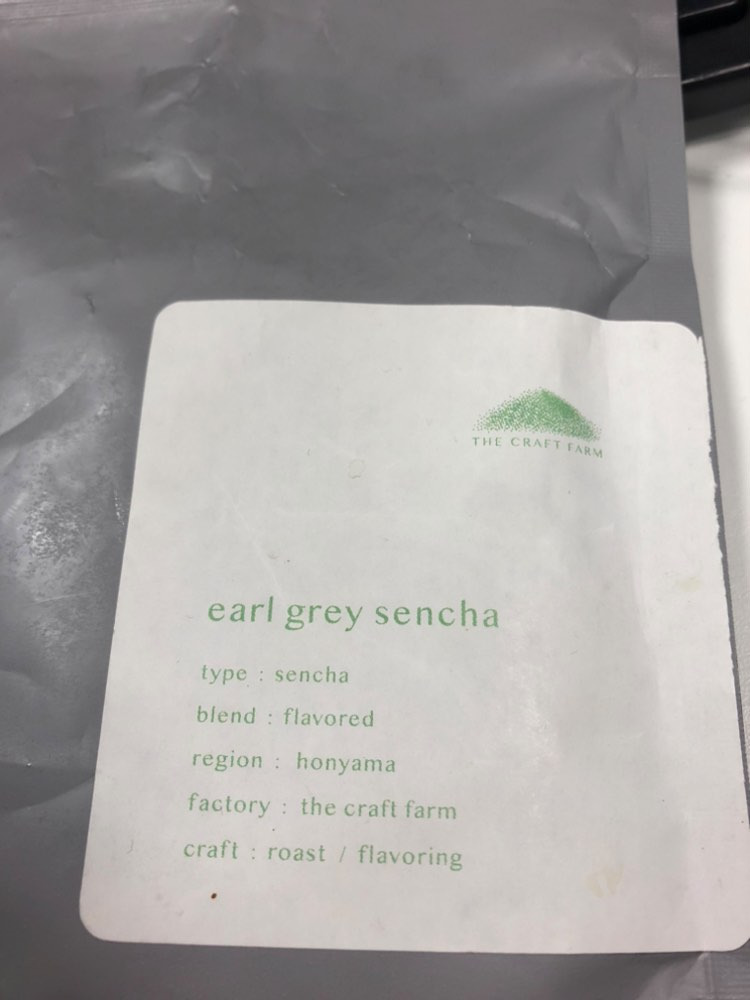

I suddenly realized I had a good supply of untouched tea bags received as gifts from Japanese visitors over the years. It didn’t take long to identify my favorite among them—a Sencha flavored with Earl Grey given to me by Barry O’Neill.

A good Sencha is like a subtle dashi with aromatic hints of roasted spinach, natural sweetness, and a hint of seaweed-like umami. In contrast, Earl Grey offers even more umami, astringency, and deep notes of peach or cherry. This tea combines the best of both worlds. “The best way to enjoy it is by cold brewing,” Barry suggested. That means submerging the tea leaves in cold water and letting them steep in the refrigerator for several hours, resulting in a smooth and delicate beverage.

Then there’s the ceremonial aspect. Esther Merino told me about her experience as a sommelier at Alchemist in Copenhagen, where they received training in Chinese, Japanese, and Taiwanese tea ceremonies, which inspired their own version for the restaurant. The tea ceremonies in these regions differ in formality, utensils, and the types of tea used, reflecting their historical origins. China values variety and Taoist influence, Japan emphasizes formality and Zen through matcha, and Taiwan blends Chinese and Japanese influences, highlighting local oolong teas.

At work, I approached my friend Furqan, and asked, “Hey Furqan, as an Indian, what can you tell me about tea?” He said, “India consumes more tea than it produces, and, in general, we can be quite rough with our tea. We boil it aggressively and add sugar. We don’t have the finesse of the Japanese. In my opinion, the Chinese excel even more in finesse. Oh, look! You should visit a place called Tadshikische Teestube in Berlin, where they serve Tadshikish tea. Tajikistan, being at the crossroads of trade routes and sharing borders with China, Afghanistan, Russia, and Mongolia, has a highly influenced and unique tea culture. You drink it on the ground and the place has a specialized tea sommelier.”

Furqan also recommended reading the legend of the origin of tea, where Shenong, the father of Chinese medicine, always made his servants boil his water before drinking it. One day, near a forest, the wind brought down some dried leaves into his water. His servants were about to discard it, but Shenong stopped them and tasted it, giving birth to one of the world’s most cherished beverages.