Copenhagen’s Renaissance: The Birth of New Nordic Cuisine

In 1987, a Danish film that would become one of the great classics of culinary cinema was awarded by the Academy for Best Foreign Language Film: “Babette’s Feast”. In it, a refined French chef arrives in a primitive Danish village where they’re overcooking potatoes and cabbage, to teach them the secrets of haute cuisine.

By that time, a young guy named Claus Meyer peddled bread on his bike around Copenhagen. By the mid 90s, he started reviving forgotten baking traditions and made a tidy fortune opening a few bakeries. Now, armed with a megaphone, he took on a big bad guy: the Danish food system. “The bread we eat is shit,” he’d say. “For ages in Denmark—and also in Sweden and Norway—making great meals for your loved ones was seen as a no-no, like stealing, getting drunk, dirty dancing, incest or masturbation.”

Back then, Denmark wasn’t a foodie hotspot. The best places served French food, with wines and cheeses imported from France. But around then, a guy named Ferran Adrià was shaking up the culinary world, challenging French hegemony and drawing Danish chefs to his kitchen. Among them was a young René Redzepi.

In 1995, a group of Danish filmmakers led by Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg gathered to challenge the established order of the global film industry. They penned a manifesto with rules to create a new filmmaking style with its own identity: Dogme 95. Something was beginning to shift in the Danish mindset.

In the early 2000s, Claus Meyer made a game-changing move. He co-founded Noma, short for “Nordic food” in Danish, with chefs René Redzepi and Mads Refslund.

A year after opening the restaurant, inspired by Ferran Adrià’s groundbreaking shake-up of the culinary world and the New Basque Cuisine manifesto from the ’70s—where 12 Basque chefs set out to define their region’s culinary identity. They wrote the Nordic Kitchen Manifesto. It wasn’t just about cooking style; it also highlighted sustainability and health by cutting back on Denmark’s meat-heavy diet.

Time Cover March 26 2012 – Cover Credit: Alfredo Caliz / Panos

Some say Noma’s success, like Adrià’s, came from chaos and tension among its founders. The constant debates and disagreements pushed them to get the best of them. In a few years, only René Redzepi remained at the restaurant. In 2010, Noma was named the best restaurant in the world according to the 50 Best list, displacing the reigning champion, Adrià’s El Bulli.

Noma’s new location location at Refshalevej 96

There might be too much romanticizing of these visionaries who, from a restaurant, sparked a culinary movement that transformed Denmark and the global hospitality elite. But it wouldn’t have happened without a key resource: money.

Enter Lise Lykke Steffensen, a farmer and advocate for diverse and sustainable food systems, who may be the overlooked hero of New Nordic Food. In the early 2010s, as a politician, wielding the manifesto, she convinced the Nordic Council of Ministers to invest heavily in a strategy forging a new food identity for all of the Nordic Countries. One that valued local ingredients over imports, specially neglected ones. From various angles—agricultural, sustainable, health, and tourism.

These funds, under Redzepi’s leadership, birthed projects like MAD, whose main goal is to equip members of the hospitality industry with the knowledge, skills, and inspiration needed to enhance their workplaces and exert greater influence on how the world eats.

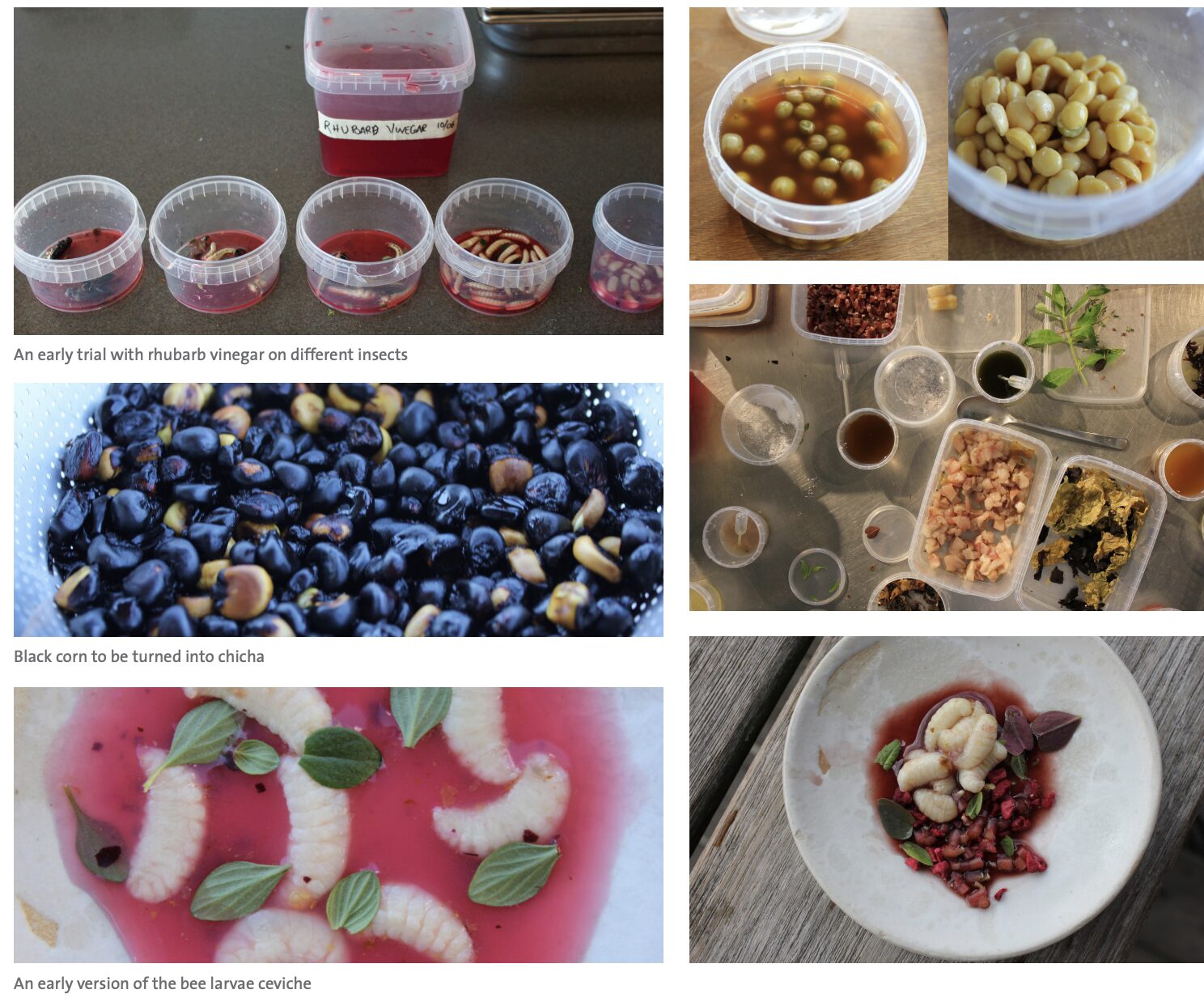

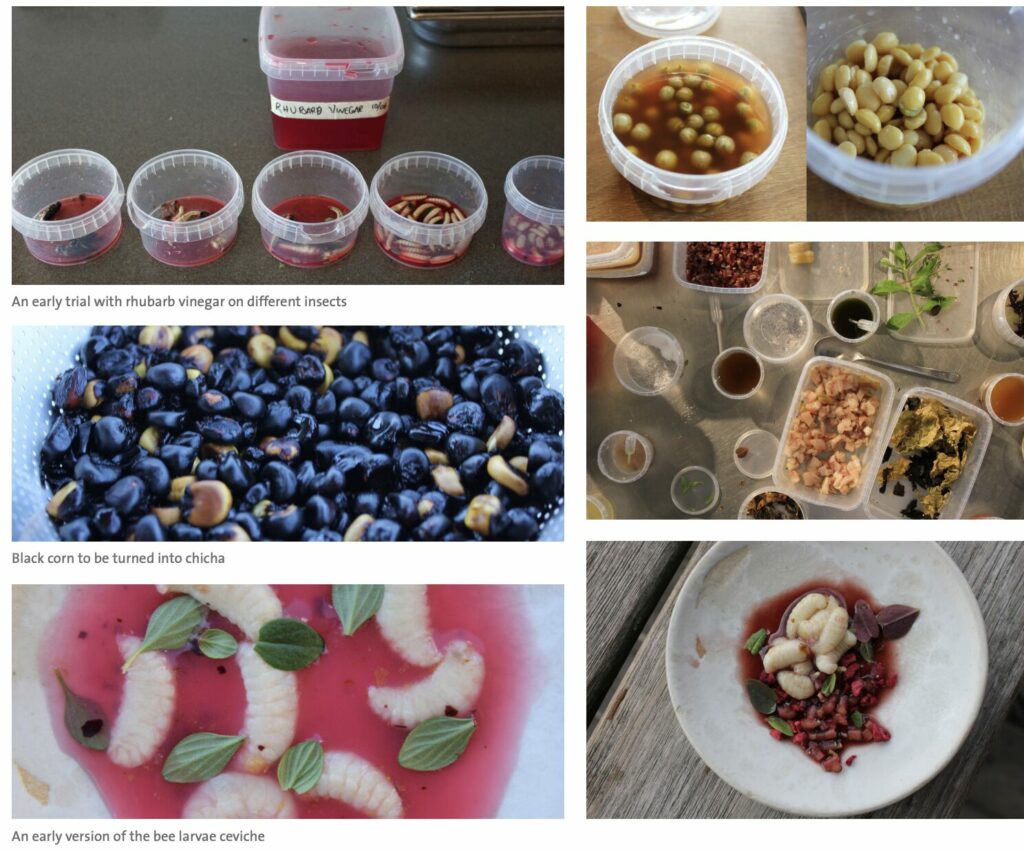

Or Nordic Food Lab, a lab aiming to reinvent eating by creating new foods from foraged ingredients, discarded fish, plants, tree bark, ants, and all sorts of underused resources. Ultimately, it reimagined Nordic food culture, replacing potatoes and sausages with fermented veggie-centric dishes.

The Nordic Food Lab Archive

Fermentation stole the spotlight in New Nordic cuisine. Funds poured into researching fermentation techniques that turned simple ingredients into infinitely complex flavors. Restaurants and then supermarkets filled with jars of fermented goodies, novel misos, insects and wines from foraged fruits.

Today, all roads lead to the manifesto, and being a food professional in Copenhagen has become a sexy thing. Its tentacles span all the Nordic countries. Many of the greatest chefs of a whole generation drew inspiration from it and chefs across the world have mimicked the Nordic style. Copenhagen’s dining scene became a museum of ex-Noma chefs and a global foodie hotspot. Definitely one of my favorite cities to eat and drink in.